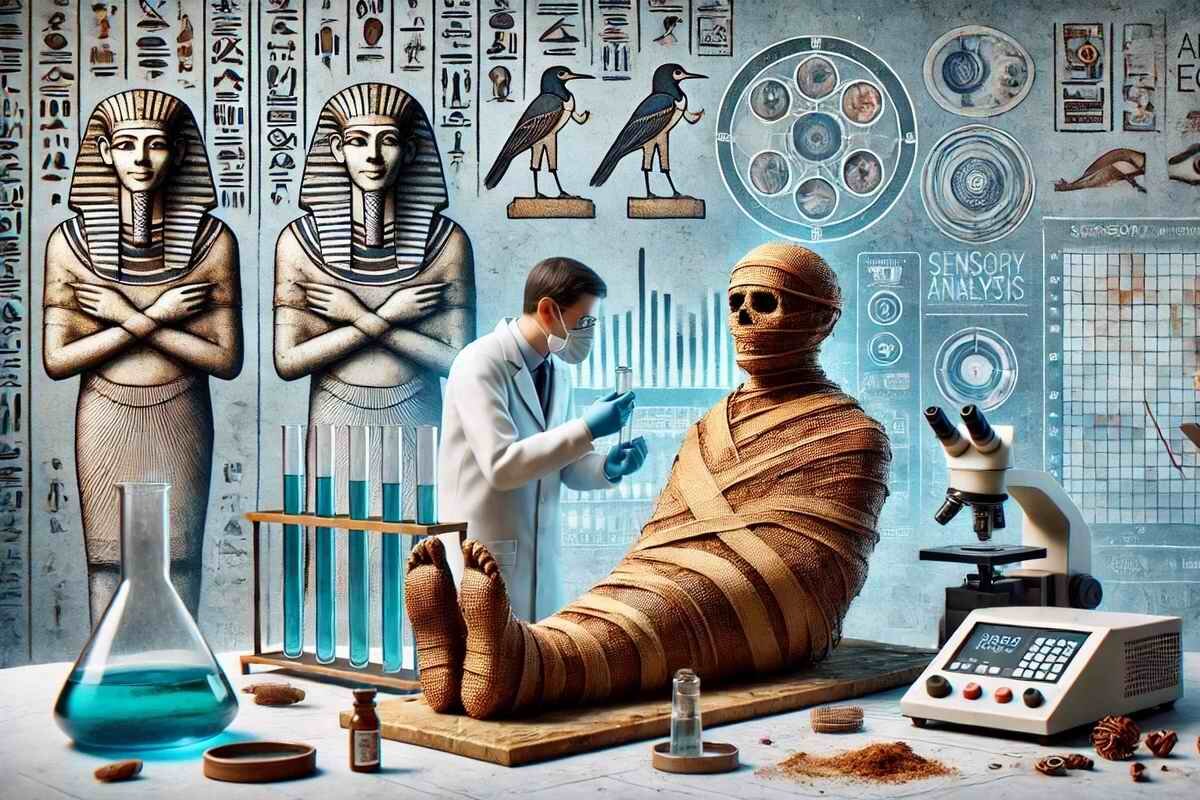

For decades, scientists have tried unsuccessfully to unravel the genetic secrets of the ancient Egyptians.

High temperatures, humidity and the passage of time have made it difficult to preserve DNA, repeatedly frustrating attempts to obtain a complete genetic sequence from individuals who lived in ancient Egypt. However, an international team of researchers has managed to sequence the complete genome of an individual who lived more than 4,500 years ago for the first time.

This breakthrough was made possible by unusual preservation conditions. The remains belong to a man buried in a sealed clay pot in Nuwayrat, south of Cairo. The tomb, carved into the rock, protected the body from extreme heat and humidity, allowing the DNA to remain surprisingly intact. This milestone offers an unprecedented glimpse into the genetic makeup of early Egyptian populations, revealing connections previously only suggested by archaeological findings. The results, published in the journal Nature, have generated great interest in the scientific community.

DNA from an ancient Egyptian human

The man, estimated to be between 4,500 and 4,800 years old, is the oldest individual from whom a complete genome has been extracted and sequenced in Egyptian territory. Analysis of his DNA reveals a predominantly North African genetic makeup, accounting for approximately 80% of his genetic material.

The remaining 20% comes from populations in Western Asia, especially ancient Mesopotamia. This genetic mix supports previous theories about cultural and commercial interactions between Egypt and the Fertile Crescent region, which encompasses present-day Iraq, Iran, Syria and Jordan.

Archaeologists and geneticists have worked for years with indirect evidence of these connections, such as the presence of similar pottery, tools and symbols in both regions. However, until now, no biological evidence had been found to confirm this mutual influence. The discovery of well-preserved DNA marks a turning point in this field of research.

According to Dr Adeline Morez Jacobs, visiting researcher at Liverpool John Moores University and lead author of the study, the results allow us to reconstruct key aspects of the man’s life, from his diet and lifestyle to his physical appearance and probable occupation. ‘We have managed to integrate genetic, bone and dental information to form a detailed portrait of this individual,’ explained the scientist.

Sequencing method

The sequencing method used, known as ‘shotgun sequencing,’ allows the entire DNA contained in a sample to be analysed, rather than focusing only on specific markers. The study’s co-author, Dr Linus Girdland-Flink of the University of Aberdeen, noted that the DNA was extracted from the root cementum of one of the teeth of this individual who lived in ancient Egypt.

Through the analysis of isotopes present in the tooth enamel, it was determined that the man grew up in the Nile Valley, with a diet consisting mainly of cereals such as wheat and barley, as well as animal and vegetable proteins typical of the region. These results are consistent with a life in Egypt since childhood, reinforcing the hypothesis that the Mesopotamian genetic influence was the result of earlier migrations.

Characteristics of the individual

Forensic analysis of the skeleton, carried out by dental anthropologist Joel Irish, revealed that the man was between 44 and 64 years old at the time of his death, an exceptional longevity for the time. Irish observed clear signs of constant physical exertion: wear on the vertebrae, bone inflammation in the pelvis from sitting on hard surfaces, and marked muscle insertions indicating work involving lifting and handling heavy objects.

Interestingly, these characteristics contrast with the type of burial received, which suggests special treatment. Burial in a ceramic vessel inside a rock tomb was unusual for working-class individuals. This has led researchers to speculate that he may have been a potter with extraordinary skills, perhaps one of the first to use the potter’s wheel introduced to Egypt at that time. Although this hypothesis is circumstantial, it is based on comparisons with Egyptian artistic representations of the period.

The data collected opens the door to further research on the population of ancient Egypt and its origins. To test whether this genetic mix was common in the region, it will be necessary to analyse other similar human remains. The study compared the man’s genome with that of more than 3,000 modern individuals and 805 ancient individuals, identifying patterns of similarity especially with populations from North Africa and the Near East.

Iosif Lazaridis, a geneticist at Harvard University and an expert in ancient DNA (although he did not participate in this research), believes that the finding shows that from very early on there was already a mixture between indigenous African lineages and peoples from the Fertile Crescent.